The boy with the golden toe -- Mariyappan Thangavelu

On the evening of September 10, 2016, when Mariyappan Thangavelu leaped 1.86 metres in the men’s high jump T-42 event at the Paralympics in Rio de Janeiro, he was making the highest jump of his life in more ways than one.

It was a leap of faith that would take him from destitution and deprivation to a world of opportunities and optimism. The gold medal that 21-year-old Mariyappan won at the event has turned out to be the proverbial silver lining of his life. Thus, when he says that the only way life has changed for him now is that he cannot walk around bindas on the streets, that people recognise him, he is just being modest.

It is his enterprising coach Satyanarayana who hits the bull’s eye on how life has changed for Mariyappan after his great feat. He says,

“Earlier, Mariyappan was dependant on his family because of his disability. Now, his family is dependant on him.”

The Jayalalitha government in Tamil Nadu awarded him Rs 2 crore after his victory. He was similarly feted by various other government bodies and corporates, and as his coach says, he is now a crorepati. He reportedly donated Rs 30 lakh from his prize money to his school.

From bottom up

One of five children born in a poor home in a village called Periavadagampatti in Tamil Nadu’s Salem district, Mariyappan did not have much going for him. The poverty at home was such that his father deserted them, leaving Mariyappan’s mother, Saroja, to fend for the family alone.

A single mother, she worked as a daily wage earner transporting bricks on her head. She later moved on to selling flowers and vegetables. When he was five years old, Mariyappan met with an accident while walking to school. A drunk bus driver crushed his right leg below the knee, leaving it stunted. In an earlier interview with The Hindu, he had said, “It is still a five-year-old's leg. It has never grown or healed."

His mother raised around Rs 3 lakh for her son’s treatment singlehandedly.

Not one to miss an 'earning day', his mother was reportedly reluctant to watch her son’s Olympics performance on television. Her other children forced her to stay back and join the rest of the village to watch the event. As the neighbourhood erupted in applause, she could not contain her joy.

The first thing that Mariyappan did after he won the gold was to call his mother. “She was very happy and started to cry,” he says, as he patiently answers a barrage of questions on the sidelines of the just-concluded India Inclusion Summit in Bengaluru.

From head to toe

A man of few words, the shy and modest Mariyappan is happy to let his coach Satyanarayana do most of the talking. “Don’t be fooled by his demeanour,” jokes his coach, adding, “no shy person can become a sportsperson.” He turns towards Mariyappan, who is grinning with his head down, his pearly white teeth lighting up his face, and asks him, “Are you shy or naughty?” He answers softly in Tamil, “Sadhu (blameless/innocent),” and the room fills with laughter.

Deserving of a Dronacharya Award, Satyanarayana epitomises what it means to be a mentor and guide. He spotted Mariyappan in 2013 when the young lad had come to Bengaluru to participate in the Indian national para-athletics championships.

A coach with a hawk’s eye to spot talent, Satyanarayana was quick to grasp Mariyappan’s potential.

Himself an international athlete, having represented India seven times on the world stage, Satyanarayana is also mentoring HN Girisha, who won the silver medal at the London Paralympic Games in 2012. He says,

“My vision is to have many more Mariyappans. There is no dearth of talent in our country. We need to ensure that we provide basic amenities and facilities to sportspeople at the grassroots level, and anything is possible.”

He should know because he himself rose from the bottom, having sold flowers from door to door.

Satyanarayana runs a sports academy for the physically challenged in Bengaluru, and says that the most important thing to remember for an athlete, whether they are able-bodied or disabled, is choosing the right event to participate in. “You must have seen the marathon blade runner today. Those blades cost a lot and cannot be afforded by our athletes. So an athlete must choose wisely depending on the kind of facilities available to them,” he says.

As any good coach, Satyanarayana knows the strengths and weakness of his prodigies. He says,

“For Mariyappan, his right toe is very important as that helps him in his jump. We have to look after it properly by ensuring it is always kept clean and not letting it get infected.”

After the accident, Mariyappan lives with a deformed large right toe, which he reportedly calls "God", as he believes it is because of the toe that he is able to achieve his medal-winning jumps.

From despair to hope

In school, Mariyappan actively took part in all sporting activities even after his accident, and could give the able-bodied students stiff competition. “He used to play volleyball. During an event in school, there were no entries in the high jump category, and Mariyappan was shifted to high jump by his school sports teacher,” says Satyanarayana.

Since then, there was no looking back for Mariyappan.

Over the year before the Paralympics, Mariyappan endured a gruelling training session under Satyanarayana. “I stopped all his studies. He just finished his final semester exam for BBA yesterday,” he says. The coach and his prodigy are preparing for the forthcoming London World Championships in July next year.

Mariyappan is staying at Satyanarayana’s academy in Bengaluru near the Kanteerava Stadium along with a few other athletes to train with a single-minded focus.

“I can say with confidence that we will come back with all medals -- gold, silver, and bronze -- from the next summer Paralympics at Tokyo in 2020.”

No hollow words these, considering that two years ago, Satyanarayana had told Mariyappan’s mother that her son would bring them gold and glory.

Clad in Indian jersey and jeans, Mariyappan sits patiently, soaking in all the adulation on the stage of the India Inclusion Summit.

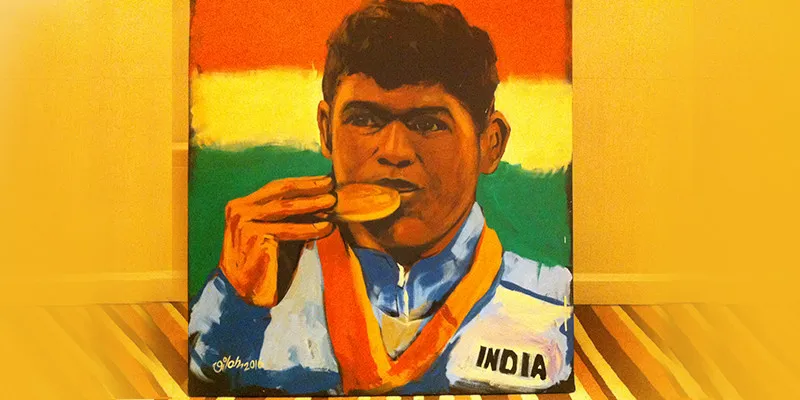

As celebrated speed painter Vilas Nayak paints Mariyappan’s portrait on stage to the beats of Bollywood’s Bhaag Milkha Bhaag song, the applause from the audience reaches a crescendo as he applies the finishing touches to the gold and Tricolour. And it is in moments like these when you know all that really matters in life is how you turn things to your advantage, even when you feel there’s not much hope.