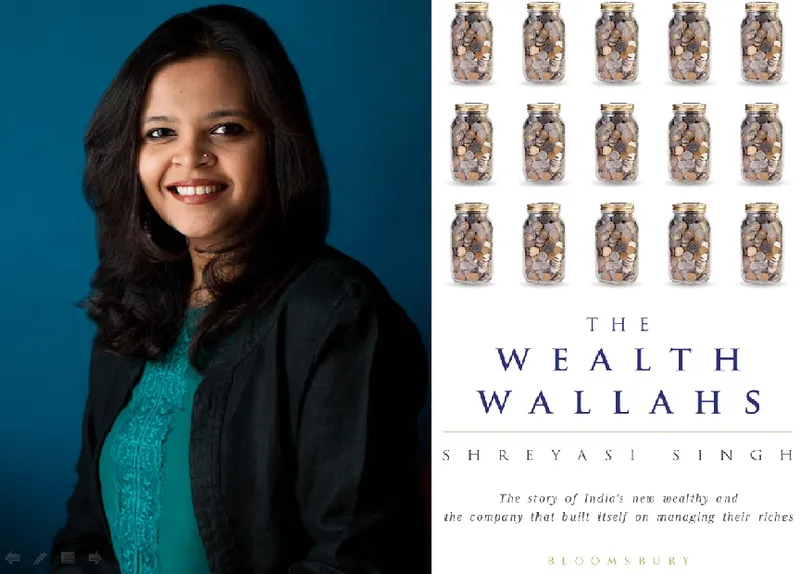

First-generation entrepreneurs need to carefully think about value, consumption and responsibility – Shreyasi Singh, author, The Wealth Wallahs

Shreyasi Singh is author of the new book, The Wealth Wallahs: The Story of India's New Wealthy and the company that built itself on managing their riches. She is Director for Careers and Programme Development at the Vedica Scholars Programme for Women, and earlier co-founded the Foundation for Working Women. She was India correspondent for ‘The Diplomat’ and graduated from the Indian Institute of Mass Communications and Lady Shri Ram College For Women.

Shreyasi joins us in this wide-ranging interview on Indian attitudes towards wealth, the startup boom, and the roles and responsibilities of founders.

YS: How did you get the idea for writing the book?

SS: A few things in the last couple of years led me to write this book. First was the many conversations I noticed happening around me. When you live in Delhi, there is great upper-middle-class angst on the conspicuous consumption of the new wealthy and the crass, ostentatious display of wealth in large pockets of South Delhi. Much of this is true, of course. What I found interesting - and often hypocritical - though was the fact that that the people complaining, including my friends and me, were also spending more and had more money to indulge than our parents ever did. It got me thinking about the lens through which we saw wealth and consumption.

In early 2012, I had met the founding team of IIFL Wealth for the first time. I was then the editor of Inc. India — the Indian edition of Inc., the American magazine on entrepreneurship. For a cover story I finally filed on them for the magazine’s August 2014 issue, I met more than two dozen of their clients. Several were first-generation entrepreneurs and senior corporate professionals. Each of them had their own fascinating story of success and wealth creation to share. They were entrepreneurs that magazines such as the one I was editing often put on the cover.

Collectively, the treasure of insights from their clients was the ‘after’ story of the entrepreneurship boom. Wealth was the happy albeit uncertain corollary of entrepreneurial and professional success. I began to realise that most reportage on entrepreneurship is limited to the process of building the business. Few articles or books focus on what happens after: the creation of wealth. When people do write about the affluent, it is to gush over their material purchases. There was an entirely new set of insights to explore. It’s what I have set out to do with this book.

This book was based on interviews, with nearly 100 wealthy creators, high net worth individuals, wealth managers and private bankers, and other people from industry who work with or think about the wealthy.

Midway through writing the book, I worried if my interviews even when they were long, fulfilling conversations had actually thrown up distorted insights. Had the wealth creators I interviewed carefully masked their real sentiments in order to sound politically correct on what their wealth meant to them?

To negotiate around this limitation, and test the assumptions I had arrived at through my interactions, I followed up the interviews with a survey of nearly sixty HNIs. I let them keep their names concealed, with the hope that the privacy would lead to more honest answers. The respondents were asked for other personal details: age, city, industries they worked in, whether they were first-generation entrepreneurs or professionals and how much they had in investable wealth, to build a character sketch. Fortunately, many of the insights from this anonymous survey mirrored the impressions I had formed through my interactions.

YS: How was your book received?

SS: It might have taken me 18 months to finish it - from research to final manuscript - but for the world the book is still new. It was out only in early October so feedback is still trickling in. The initial reactions have been heartening. There is clearly an appetite for understanding both the themes the book talks about: creation of wealth and the entreprenuership journey of a wealth management firm. It’s been wonderful to see the book make it to some ‘must-read’ lists. Writing a book is long and often dispiriting; you learn to enjoy every small mention!

A somewhat negative review I got on Amazon said that the book only scratched the surface; that while it was laudable for the book to attempt to deconstruct how the wealthy thought about their riches, the insights could have been more profound. Heartbreaking as that review felt, it points to the challenges I speak about earlier. It also indicates that there is an urge to understand the notion of wealth in a fast-changing country.

YS: In what ways has traditional Indian philosophy shaped attitudes of Indians toward wealth?

SS: As a country, India has a complicated relationship with wealth. Through much of the nearly seventy years of our nationhood, we have lived on the wholesomeness and worthy goal of having just enough. A craving and indulgence for wealth was neither encouraged nor possible in an economic philosophy built on the idea of socialism and where the government controlled and regulated private enterprise.

It has been a country where the vast population was poor with a minor middle class, an extremely tiny portion wealthy, with rigid lines dividing them all. Mobility across these different segments was limited. Since lines were not porous, attitudes within each group — and towards each other — were more fixed and unyielding.

Traditions and history have been powerful shapers of thoughts around wealth as well. Our civilisational heritage also points to a certain discomfort with wealth. Indian philosophical thought is rich in ideas about wealth. The idea that money is useful and necessary for human progress but potentially damaging and untrustworthy when privately hoarded is the central theme of how we view those with wealth.

YS: How has interaction with the West, particularly in areas like tech and startups, changed Indian attitudes towards wealth?

SS: One of the books I read for my research was Money, Morals and Manners: The Culture of the French and the American Upper-Middle Class by sociologist and author Michele Lamont. In this fascinating book, she explores the nature of social class in modern society. Through interviews with 160 successful men in the US and France — managers, professionals, entrepreneurs and experts — she has revealed a collective portrait of the value and attitudes these men consider as setting them apart from others.

On the topic of money, she draws interesting contrasts between her French interviewees’ ambivalent-to-condescending attitude towards money, and its lesser importance in determining class than in the US where professional success is measured more by income level than by nomination to prestigious positions. The Americans also see money as an essential means to control and freedom, a way to emphasise self-actualisation and interpersonal relationships without belittling money the way the French often do, Lamont writes.

Surprisingly, the American mindset was mirrored by many interviewees of my book as well. The new Indian wealthy (especially, entreprenuers) has much in common with the portrait of the well-to-do American that Lamont has sketched. For example, even for those reluctant to talk about their wealth, there is no ambivalence about having made the money. Yet, while wealth does determine success in some measure and liberates them from fears and limitations, it was neither the end-goal nor the sole currency of social status. So, even as the new-generation wealthy conceded that in social settings and business events, people might size each other up on the basis of their personal wealth, their status in a group wouldn’t come only from that.

But, where Western start-up icons (often, mostly American), have impacted the way first-generation technology entreprenuers look at business and wealth is philanthropy. Prompted by the highly-publicised Giving Pledge — a commitment by the world’s wealthiest individuals and families to donate the majority, philanthropy has definitely become a more mainstream issue in the world of business. While old industrialist families in India always did charitable work by way of temples, schools and health care centres in the villages they belonged to or the areas where their factories were located, the quantum of personal wealth given away is a new dimension now. First-generation rich are giving both wealth and time before the inheritors, and were doing so earlier into their wealth journey.

YS: How do the current crop of Indian entrepreneurs and professionals differ in terms of wealth management attitudes and practices, as compared to earlier generations?

SS: This is a very interesting question. My research found that both the pace of creating the wealth as well as the quantum of wealth influences mindsets and aspirations. Much of the accelerated pace of new wealth in India has come from individual business ownership. In fact, first-generation entrepreneurs have injected a great deal of dynamism into the industry and, in many ways, are changing how it works. As a customer segment, wealthy first-generation entrepreneurs have not only expanded the size of the wealth management market but are also rewriting the rules of the game.

On innate risk appetite, for example, they differ substantially from the traditional wealthy, especially those from the third, fourth or fifth generation. Their general risk appetite was higher. Often, they were younger too. They chase growth rather than just focusing on maintaining asset levels.

First-generation entrepreneurs’ can-do attitude has evolved from the fact that they have seen their lives change within a decade or so, if not years. Their focus on wealth creation comes from the greater ambition and aspiration levels consolidating across India as well as a belief that dreams can come true.

YS: What are the top three challenges entrepreneurs face after they secure funding from a VC or are acquired by another firm?

SS: I was surprsied that several young entrepreneurs, even those educated in pedigreed management colleges, hadn’t been introduced to, or thought about, the concept of wealth management. One told me - almost sheepishly - that till his internet venture was acquired and he had to figure out how to manage his new found wealth and identify wealth advisors to help him do so, he thought all the rich did was buy things. That is the first challenge for entrepreneurs: they need to anticipate these life changes and use the opportunity to manage their wealth. A senior private banker told me he is often appalled by the low level of financial savvy, even successful and educated Indians have.

Second, not enough people understand the personal complications that money decisions, or wills and trusts that need to be made, can have on relationships. These decisions require honest conversations, and an articulation of personal goals, family obligations and future plans. The discipline to sit down and do this

Another challenge entrepreneurs might face if they come into a large tranche of personal wealth is the market environment. Over the past few years, the wealth management industry in India has become hyper-competitive: large banks, brokerages with portfolio management systems, independent financial advisors, boutique firms and pure-play wealth management outfits have all emerged to participate in the opportunities new wealth and the new wealthy have put to offer.

In the metros and large business hubs, almost every potential and existing wealth management client I met complained bitterly about being bombarded by cold calls from what a Bengaluru-based entrepreneur described as ‘a formidable, can’t-be-swatted-away battalion of cold-callers, emboldened by every rejection, encouraged every time the phone is hung up on them.’ Wading through these can be irksome, tiring and time consuming.

YS: How do Indian entrepreneurs differ from their counterparts in the West and China in terms of wealth management?

SS: The Indian saving mindset comes from an incredibly strong value-for-money orientation. In particular, it’s ingrained in the DNA of its first-generation wealthy. An affluent Indian customer is both demanding of quality, especially of service, yet deeply influenced by the price. They bring this mindset to the way they manage their wealth, and the relationship they strike with their wealth advisors.

A senior private banker who worked in New York for several years and today spends more than half a month across the world’s top financial centres told me that the value-for-money focus of his firm’s clients in Mumbai was rather striking compared to other cities. They are also more hands-on as investors, possibly because they are doing it the first time and are used to being hands-on, operations people who built their businesses from the ground up.

YS: What is driving the surge of the wealth management industry in India? How would you describe the New Wealth Builder (NWB) market?

SS: India has witnessed an unprecedented phase of wealth creation over the past two decades, a trend that has sharply accelerated in the past ten years. India’s wealth increased by $2.284 trillion (Rs 15,24,227 crore) between 2000 and 2015, making it one of the world’s fastest growing economies with a 211 per cent increase in overall wealth, according to Credit Suisse.

A growing number of equity dilutions, stake sales and real estate deals have led to this never-before pace of wealth being created and unlocked in India; it has also given way to the emergence of a new group of the first- generation wealthy. Be it cut-throat deals or generosity, it’s the new wealthy who are making waves.

Let’s take a look at Shanghai-based Hurun’s India Philanthropy List of 2014, for example. Seventy-three per cent of the people named on the list, on the criteria that they must give away Rs10 crore ($1.5 million) or more in philanthropy, were self-made. India’s economic progress has provided the bedrock for this growth, expanding as it has from being a $1-trillion (Rs 66,73,500 crore) economy in terms of its GDP in 2007 to double of that by 2015.

The rise of these groups has made India the world’s most fertile breeding ground for the wealthy. Interestingly, India seems to be minting wealth across a wide spectrum, from the ultra to the moderately wealthy. The number of both high net worth individuals or HNIs (those with more than 6.5 crore, or $1 million in investable assets) and ultra high net worth individuals or UHNIs (those with more than 25 crore, or US$ 5 million in investable assets) is rapidly climbing.

According to the World Wealth Report 2015, India recorded the largest gains — in the Asia-Pacific region and globally — in the HNI population (26.3 per cent) and wealth (28.2 per cent). Simply put, the wealth effect in India is leading to growth, both in the number of HNIs and an increase in the total quantum they have amassed.

By 2018, India will be home to 3.58 lakh millionaires, more than doubling its tally from 1.8 lakh in 2013. Another study has found that over the next four years, the number of New Wealth Builders (NWBs) — Indian households with financial assets of $100,000 to $2 million (Rs 66,73,500 to Rs 13 crore) — is expected to jump ten-fold to 4.9 million. This is ripe picking ground for the wealth management industry.

YS: Who are the leading players today in India in wealth management? What are the key success factors in this field?

SS: There are no established league tables in India’s wealth management industry. Wealth management companies, in fact, differ even on the definition of assets under management (AUM). Some include promoter assets, credit given to clients and inactive assets that they don’t really manage. Since the AUM is a self-declared figure, and one that each company tabulates on its own, it is difficult to be certain how the companies stack up.

Over the years, there is high concentration at the top and most private bankers agree on a rough pecking order although exact numbers are difficult to come by: IIFL Wealth and Kotak Wealth Management make up the top with more than Rs 80,000 crore ($11.9 billion) in AUM each, followed by Julius Baer (India) at about 25,000 crore ($3.7 billion) reportedly. The third level is made up of Anand Rathi, Edelweiss, RBS,ASK, Client Associates, all of which have approximately 10,000 crore– 20,000 crore ($1.4-2.9 billion) in AUM.

There are also hundreds of thousands of Independent Financial Advisors (IFAs), boutique wealth management firms and other institutions (retail banks and tax consultants) that offer parts of the traditional private banking-type services.

YS: What regulatory changes are impacting wealth management?

SS: In the eighteen months alone that I worked on the book, the landscape of the wealth management business has changed. Regulation has evolved quite rapidly — the general direction being towards making the business more advisory-focused, less commission-led. The aim is to ensure that clients get objective advice that is devoid of the lures and temptations of the commissions doled out by creators to the sellers of products.

Much like the confluence of the wealth effect and the ruptures in the global financial services industry created new vistas for growth, the current changes in the wealth management industry come from the combination of both the clients and regulators displaying greater maturity.

The changing nature of the industry has made the entry barriers to the business tougher. New players will need more capital to start off now, since they can’t rely on the quick revenue that comes from commissions. Asset management and advisory fees are usually structured on an annual basis. A company must be capitalised enough to offer client services and be able to wait it out for fees to come in.

Keeping pace with these forces will be critical for a big firm if it doesn’t want to lose clients. This convergence has provided a natural advantage for independent advisors and boutique firms because they can pivot to the new regulations without having to overhaul their technology and systems.

YS: How has technology such as online resources affected wealth management?

SS: In a November 2015 article, Bloomberg News had noted the emergence of ‘robo advisory.’ The article had said that the automated investment platforms industry has seen dramatic growth, from almost zero in 2012 to a projected $300 billion in assets under management at the end of next year. It forecast that robo-advisors could manage $2.2 trillion by 2020.

Technology hasn’t disrupted the wealth management space in India yet as clients still largely use technology as dashboards to monitor their investments and portfolios. A technology-driven platform that can take over the advisory aspect hasn’t yet been a disruptive force. It might happen though.

Global examples of companies such as Charles Schwab, FutureAdvisor and Personal Capital show that in the mass-affluent segment, ‘robo advisors’ are beginning to play a more dominant role in substituting human advisory. Such a disruption in the wealth segment — led by a smartphone application, for example — could change the market environment substantially.

YS: What do entrepreneurs need to learn about wealth management when they themselves become angel investors or philanthropists?

SS: India is one of the world’s most unequal places. The Credit Suisse report on global wealth, referenced earlier, found that the richest 1 per cent of Indians owned 53 per cent of the country’s wealth; and that the richest 5 per cent owned 68.6 per cent of the country’s wealth while the top 10 per cent had 76.3 per cent. Worse, the gap between the wealthy and the have-nots was widening.

In 2000, India’s richest 1 per cent owned 36.8 per cent of the country’s wealth while the share of the top 10 per cent was 65.9 per cent. The gap in India was also bigger than the one in other countries. The share of India’s richest 1 per cent is far ahead than that of the top 1 per cent of the US who own a mere 37.3 per cent of the total American wealth.

India’s wealthy seem to understand the atmospherics of inequality. Although my intention in most interviews I conducted for the book was to talk about views and attitudes to philanthropy only at the end of the conversation, in seven out of ten discussions roughly, it would be brought up much earlier. Clearly, there was an eagerness to engage with the issue of philanthropy, or certainly an eagerness to be seen to engage with it. The truth though is that while many do participate in an ad-hoc way in orphanages, causes and non-profit work, few walk the talk in terms of making a cause a mission.

YS: What are some key emerging trends you see in wealth attitudes and management in the coming years?

SS: Success in the risky world of wealth management hinges on trust. The circle of trust gets built client by client but can be destroyed far more quickly. A few client relationships can mar a company’s reliability. Personal reputations can suffer swiftly. The organised wealth management industry might be saner than it was in the years before the global financial crisis of 2008 but it continues to be volatile, ambiguous and complicated.

For one, attitudes towards wealth might well change in the first-generation wealthy. It is an unpredictable, whimsical group, still getting used to creating and managing wealth. To assume that it has settled into a template would be a mistake. Clients’ expectations from their wealth advisors are always a work in progress as are the relationships they enter into. The first-generation wealthy want high returns and push their wealth managers to show them exciting products that can deliver big on high expectations.

The metrics and avenues for performance might change completely as well. For example, technology could and will possibly be a big disrupter. A key trend in wealth management also is that clients are galloping ahead by years in their education of the financial advisory business. Newer clients are more demanding of transparency. Most question their advisors on the incentive structures that relationship managers work with, or the product commissions the firm gets. The increased competition, a more aware client base and fresh regulation governing the space has opened up several options for clients.

YS: What is your next book going to be about?

SS: If you had asked me this question four months back - when I was editing The Wealth Wallahs - I would have stridently declared that I would never write another book. It’s too much hard work. It takes too long. It occupies too much mindspace. Author friends had told me that I should adopt a ‘never-say-never’ response to this question. Many told me that nobody stops at their first book.

I didn’t believe them then but I have to confess that I am already thinking about - and talking to publishers - about two ideas I have. The one I am more passionate about, and hope to get started on first, will be a children’s book. I have a 10-year-old son and writing a book for him and others his age is something that really excites me.

YS: What are your recommendations or tips for the entrepreneurs in our audience?

SS: Bain Capital’s Amit Chandra, who I interviewed for the book said the fresh spurt of entrepreneurship has helped counter the complicated mindset around wealth to a certain degree. He said that the pendulum had begun to swing a little, especially in the past fifteen years, as professionals become wealthy and new enterprises come up in sectors that are perceived to be less corruptible thus improving business transparency. The value of money and what it can do — create jobs, build products and expand markets — has given the pursuit of wealth more respectability.

Today’s generation of entrepreneurs must keep this in mind. As they build profitable businesses in India, they must be conscious that the way they think about value, consumption and responsibility will drive notions and attitudes towards wealth. That way of thinking can hopefully drive a powerful sense of accountability. It can help deepen ambitious, high-potential entrepreneurship.