Online education and why we are a long way off from Saraswati and Lakshmi

The industry is expected to grow to $5.5 billion in market size by 2020. But there is very little focus on outcomes and there is danger of focusing on business models that go after 'loss-making' market share.

Everybody seems to be obsessing over the myriad troubles of the e-commerce industry these days. The discourse has shifted from stratospheric valuations of home-grown e-commerce companies to their unit economics and cash flows. The chorus of criticism for their profligate ways has grown by the day, and media has kept an unblinking watch over the smallest of developments at these companies. In this whole preoccupation with the e-commerce companies, the distress signals coming from the online education industry, which has been showing the same symptoms as the e-commerce industry, seem to have gone largely unnoticed.

A case in point is TutorVista, which reportedly is again up for sale. When Pearson PLC acquired TutorVista from its founders K. Ganesh and his wife Meena in 2011 for $127 million, the sale had made news for being one of the biggest exits by an Indian education company. Now, Pearson is planning to exit the consumer or retail education business in India, and if sources are to be believed, TutorVista has been put up for sale at a price that is considerably lower than the $127 million that Pearson had paid for it. Pearson, on its part, has however preferred to remain tight-lipped about the proposed sale. An email sent to the group's Indian operations did not evoke any response. The company has reportedly not been able to scale up its technology and promise of online tuition being the panacea for students across the world.

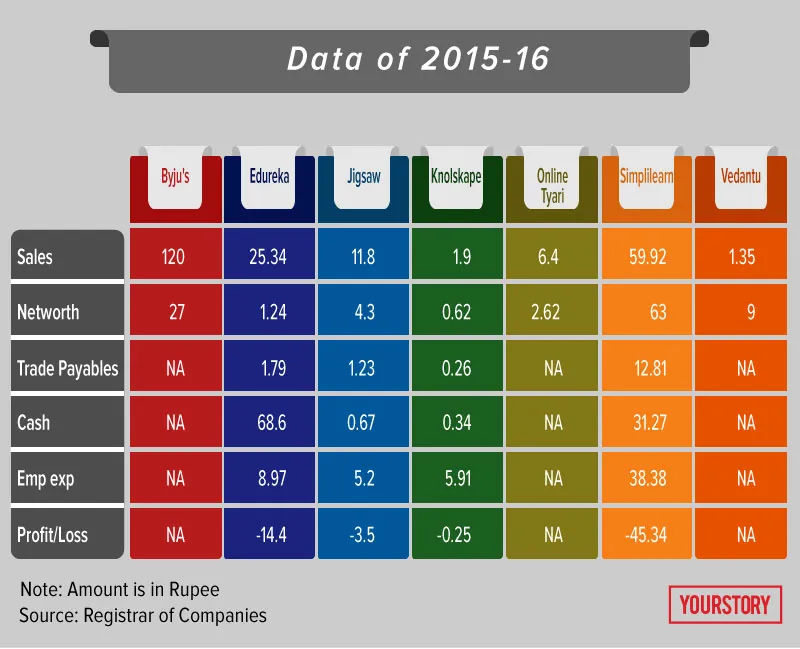

When one looks at the online education industry today, one cannot help but get a sense of deja vu. Like the e-commerce industry, the ed-tech sector appears to have tied itself in knots chasing market share instead of focusing on outcomes. An inordinate amount of money is being spent by ed-tech companies on creating mind share. Looking at Byju’s TV creatives, for instance, one would believe that mobile-based consumption of education has truly arrived. But a glance at the financial data of all the top ed-tech companies shows that they are all bleeding (see chart).

The guzzlers

Data available with the RoC shows that some of the ed-tech companies are just guzzling cash. They are either paying high rentals, probably because a major portion of their business comes from brick and mortar approach to teaching, or they are spending a lot on customer acquisition or both. The pertinent question to ask is: When will Indians start paying for online courses on a mass scale? Until people start doing so, the revenues of all ed-tech companies, combined, will go on showing dismal growth.

While the press never ceases to romanticise the power of mobile-based education services to revolutionise teaching in India, the ed-tech companies have thus far concentrated all their efforts on increasing the market share to the complete neglect of outcomes. At this rate, technology will become just another channel for the delivery of certificates, with little or no bearing on the quality of education.

The country will continue to have an ever-increasing army of “educated, but not employable” youth. The ed-tech industry is making the same mistakes that the country’s schools and colleges have committed all these years -- going after numbers instead of value-based teaching.

The industry, however, believes that it is being responsible and is focused on larger outcomes in the long run. “Ed-tech companies or online courses need more than ten years to a build a brand. They will not make money in the short run. And yes, the approach should be outcome-based. Outcomes could mean skill development programmes for professionals or preparing students for employability,” says Gaurav Vohra, Co-founder of Jigsaw Academy, which trains people in data sciences and prepares professionals for a larger role in analytics.

Gaurav says that the industry should have a long-term view and focus on outcomes rather than going after market share which represents the number of students added on a platform. Jigsaw Academy will close the financial year 2016-17 with Rs 16 crore in revenues.

“Today institutions are the real competition. They have the long-term capital and vision to take on ed-tech. In fact, we are witnessing a hybrid model emerge in schools and colleges where institutions are also signing up with online service providers,” says Gaurav.

It’s been six years since the top ed-tech companies hit the market, but they have yet to make money. Byju’s, which refuses to share its profit or loss numbers, says its revenues are going to double this year. But sources say that the offline portion of the company’s revenues is way more than the online revenues. The same is said to be the case with Simplilearn; its topline is growing, but not the bottom line. According to a FICCI-E&Y report, India has the lowest gross enrolment in education, which is 22 percent, when compared to 90 percent in the US.

Here are some of the key challenges facing the ed-tech industry:

- Changing student behaviour to go all-mobile is not working.

- Everyone downloads apps, but there are no paying customers.

- Institutions are competing with ed-tech companies and have money for the long run.

- Too much money is chasing cost-effective courses rather than outcomes.

- The industry is competing with each other rather than planning to take on large institutions.

- They are yet to make any profits out of their customer base.

OnlineTyari, which has more than 3,00,000 daily active users, believes it is making an impact on the diaspora from smaller cities and towns who aspire to join banks, railways and other public sector companies by writing competitive exams. “The need for outcomes is massive and skill development programmes can make a large impact if students can get jobs,” says Vipin Agarwal, Co-founder of OnlineTyari.com. Banking and railway exams have close to 2.75 crore takers each year and OnlineTyari is going after this segment with mobile-based test preparation modules, which also includes carrier billing.

Vipin believes there is enough interest in smaller towns and that if the usage is simplified along with the payments then outcomes on smartphone-based education will increase.

The big bets

The Manipal Group and investors like Aarin Capital and 3One4Capital are betting big on outcome-based approach to education and are willing to stay on for the long term. However, they too concede that it is the founding team that needs to decide between growth and outcome; it is a subtle balance that they need to achieve. They have invested in Byju’s, Online Tyari and Jigsaw Academy. “Education is where technology can make the most impact and help reach a multitude of individuals,” says Mohandas Pai, Founder of Aarin Capital.

According to consulting firm Technopak, the Indian education market is currently estimated to be $100 billion in size. It pegs online education market as a $2-billion-dollar opportunity and expects it to grow to $5.7 billion by 2020 when the total spend on education will be around $180 billion.

The challenges India’s education system faces are mammoth. The UNESCO estimates that there are 1.4 million kids aged between 6 and 11 years that are out of school as of 2013-14. According to the IBEF, the country has more than 1.4 million schools with over 227 million students enrolled.

While the country has one of the largest higher education systems in the world with more than 700 universities and 35,536 colleges, there has been no disruption in the approach to education. The online education streams have not yet lived up the expectation of being the disruptors they were made out to be.

The journey is not going to be easy for the ed-tech industry and their founders for sure, as they have to walk the fine line between managing cash, customer acquisition and expansion and achieving outcomes for students. It feels like the “impossible trinity”, which in economics means that it is impossible to have an economy where there is free flow of capital, a fixed exchange rate and an independent monetary policy.

But in the meantime, the ed-tech companies must realise that it is about time they changed their approach to business to focus on the outcome rather than the outreach, for only then will they make Indians truly skilled and employable.

Which domain name would you choose for your website? Click here to tell us.