This 80-year-old retired IAF captain is providing shelter to elderly homeless women

Captain AC Barua runs Seneh, a home in Guwahati that provides shelter, food, healthcare facilities, and clothing to homeless and abandoned elderly women and helps them lead a life of dignity.

Last month, A C Barua, a retired IAF captain who runs a shelter home for elderly women, received a call about a middle-aged woman who had been found in a distressing state at a makeshift shack in Guwahati.

The captain immediately sent his team to the location where they saw the woman living in a dilapidated shack, amid squalor and unhygienic surroundings. Her legs were swollen and her body was covered in dirt. She had been living in the shack for a few months and came out only to beg for food.

Though she was initially reluctant, the woman eventually agreed to go with the team to the shelter home.

“When we brought her in, it became evident that she was grappling with mental health challenges. Her speech is a constant stream of words that does not make any sense. But she is a very fun, spirited lady,” Barua shares with HerStory.

“We affectionately call her Rangili, because she always keeps dancing and singing," he says, adding that Rangili keeps the mood light and happy in the shelter home.

Rangili is one of the many women living in Barua’s shelter home in Guwahati.

The shelter home for homeless elderly women—called Seneh—was established in 2011, under the Bhavada Devi Memorial Philanthropic Trust, named after the captain’s mother. Since then, the home has provided a roof to over 100 women from Assam, Jharkhand, Bihar, and Telangana.

“Many elderly women are left abandoned and starving on the streets. Some also suffer from mental health issues and often get lost. We bring them to our shelter and try to reach out to their families. If the family refuses to take them back, we give them shelter for the rest of their lives,” explains Barua.

The beginning

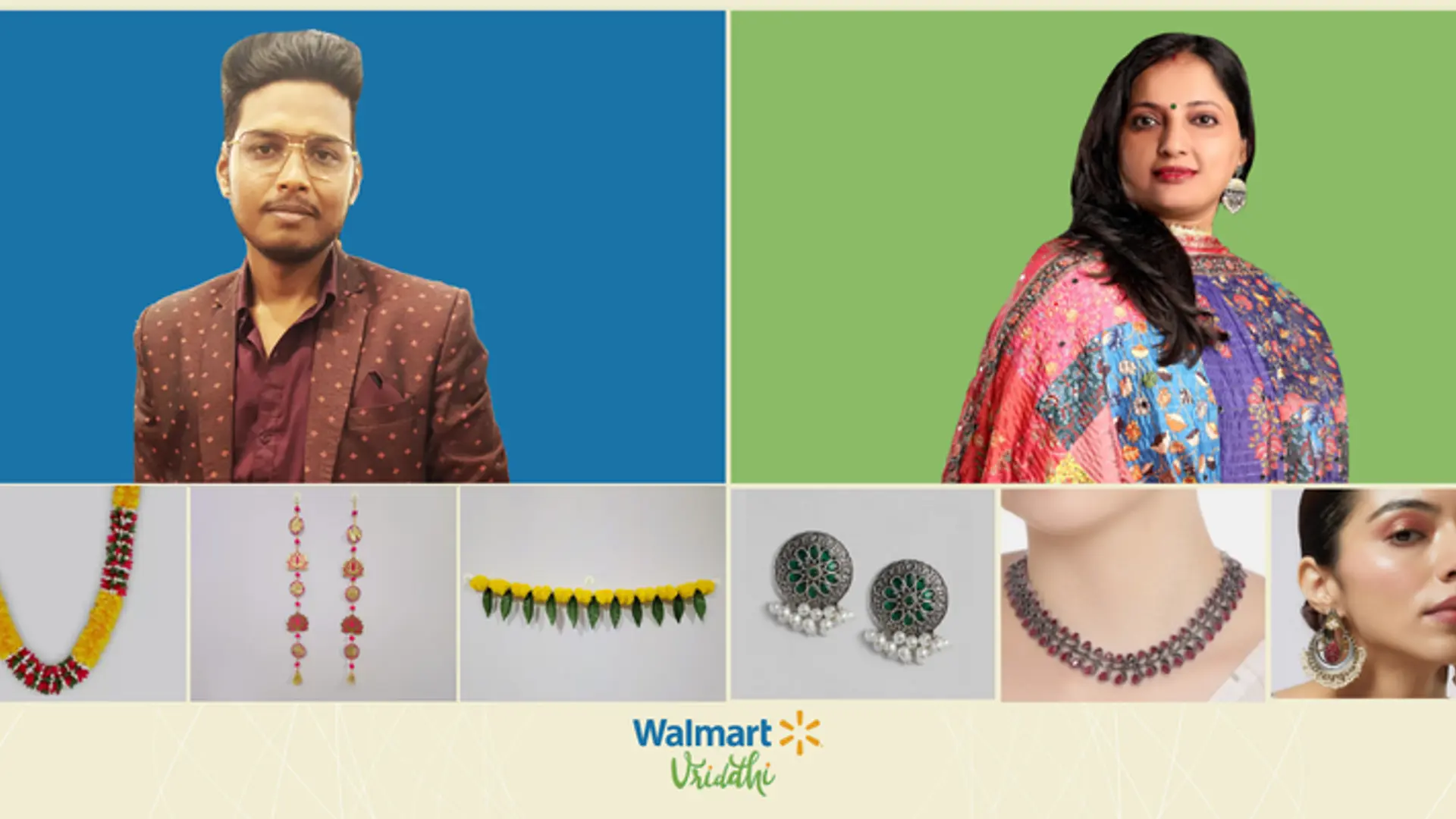

Captain AC Barua

Barua worked as an aeronautical engineer with the Indian Air Force for three decades before taking voluntary retirement in 1999. He then started a cargo business along with a friend, a former diplomat.

After eight years, when his friend died of a heart attack, Barua did not wish to continue with the business alone. He shut down the business and plunged into social service.

In 2007, Assam experienced catastrophic floods that wreaked havoc in many rural areas, leading to extensive damage to homes and agricultural fields and the loss of many lives. Moved by the plight of the people, Barua, who hails from Jorhat district, decided to visit the affected regions.

As a member of the Assam Educational and Cultural Trust in Delhi, he travelled to various flood-stricken parts of the state to engage in relief efforts. While on a visit to a remote area, he stumbled upon a dilapidated shack, surrounded by water. He found soot-covered utensils, a torn mosquito net, and a few dirty clothes hanging from hooks.

Inside the shack was an old lady and her crippled son lying on a cot.

“I could never imagine that someone could live inside that place. The whole scene was heart-wrenching … I cannot forget the hopeless look on her face,” says Barua.

“The lady had no one except her son, and since he was bedridden, she could not leave him. The house was also surrounded by so much water that she had no option but to stay inside their collapsing home.”

The captain helped the woman and her son to get out of the hut to a safer place.

Long after the incident, the image of the suffering mother and her son remained etched in Barua’s memory. So, one day, he decided to establish a safe space for elderly women.

By this time, he had earned enough money from his business and this helped him set up the shelter home.

Barua bought a plot in Guwahati and constructed a five-room house to provide shelter for women.

A year later, Seneh had its first resident—an old lady named Priyo Bala, who had lost her husband and had been living alone in a remote region near Guwahati.

Bala had been a construction worker, but her legs were broken in an accident. She had no one to care for her, except a few neighbours who offered her one meal a day.

Barua and his team at Seneh brought the lady to the shelter home where she underwent six months of treatment.

Soon after, the team brought in a tribal woman who had been physically assaulted by the villagers who accused her of practising witchcraft.

Since then, there has been no looking back for the captain and his team.

“Word spread and people started calling us,” says 80-year-old Barua, who is lovingly called Deuta’ (Assamese for ‘father’).

Impacting lives

Seneh takes in women above the age of 50, who do not have anyone to care for them, have been abandoned by their families, are mentally unwell with nowhere to go, and do not have any means of sustenance.

The home can house up to 30 women at a time and provides shelter, food, healthcare facilities, clothing, and other necessities to help women lead a life of dignity.

Barua helping a visually impaired lady

Barua recalls the story of Rajbonti, who is nearly 70 years old. Originally from Bihar, Rajbonti and her husband had migrated to Guwahati. After the loss of their daughter, Rajbonti couldn’t conceive again. Subsequently, her husband left her and married again.

Rajbonti resorted to begging to sustain herself. The president of a women’s club noticed her plight and brought her to the club, where she was given the job of a cleaner and caretaker. She lived there until her memory started fading. When her health deteriorated, she was brought to the shelter home.

Rajbonti was diagnosed with dementia, and soon she lost control of her bladder and bowel movements. She has been in the shelter home for a year now, undergoing necessary medical treatment.

Safe haven for elderly women

The shelter identifies women who need help through local police reports or concerned citizens. The Railway Protection Force also alerts the shelter home about abandoned elderly women.

Seneh ensures the women are engaged in some activity or the other and remain self-reliant. Those who are physically fit take turns to cook food, while others help in chopping vegetables and cleaning utensils.

The shelter home also encourages activities such as knitting, embroidery work, weaving, singing, pickle making, and yoga, based on the residents’ interests.

The products made by the women are sold in the local market and the money generated is spent on their entertainment. Recreational activities include picnics and visits to nearby places of attraction.

Barua explains that about 70% of abandoned women face mental health problems such as dementia and need psychiatric medication. There are also women dealing with cancer and heart issues, while some have physical disabilities.

To provide treatment to these women, the shelter home has partnered with Sun Valley Hospital and Dr Bhubaneswar Borooah Cancer Institute in Guwahati. It has also tied up local doctors who provide free treatment to these women. A psychiatrist also visits the home twice a week.

Barua giving medicine to a lady

Barua has a team of seven employees who stay in the home 24/7 to take care of the inmates.

The upkeep of the shelter costs Rs 2 lakh a month. Barua has been running the shelter with his own money and his son’s help. Additionally, Seneh also receives funds from crowdsourcing and donations. Groceries are donated by kind-hearted people.

“Everybody in and around Guwahati knows about our work, and many of them have also come forward to help us. I just hope things continue like this when I am no longer around,” says Barua.

Edited by Swetha Kannan